In today’s substack, I would like to look at the Baal cycle in more detail, with further cross-references to the ministry of Jesus.

The Baal cycle is a collection of ancient Canaanite mythological texts that depict the exploits of the storm god Baal. The cycle consists of six major episodes, each showcasing Baal's divine power and his struggles against his enemies. These texts were discovered in the ancient city of Ugarit, in modern-day Syria, and are dated to the late Bronze Age (ca. 1400-1200 BCE). The Baal cycle is one of the most important literary works of the ancient Near East and provides valuable insights into the religious beliefs and practices of the Canaanite people.

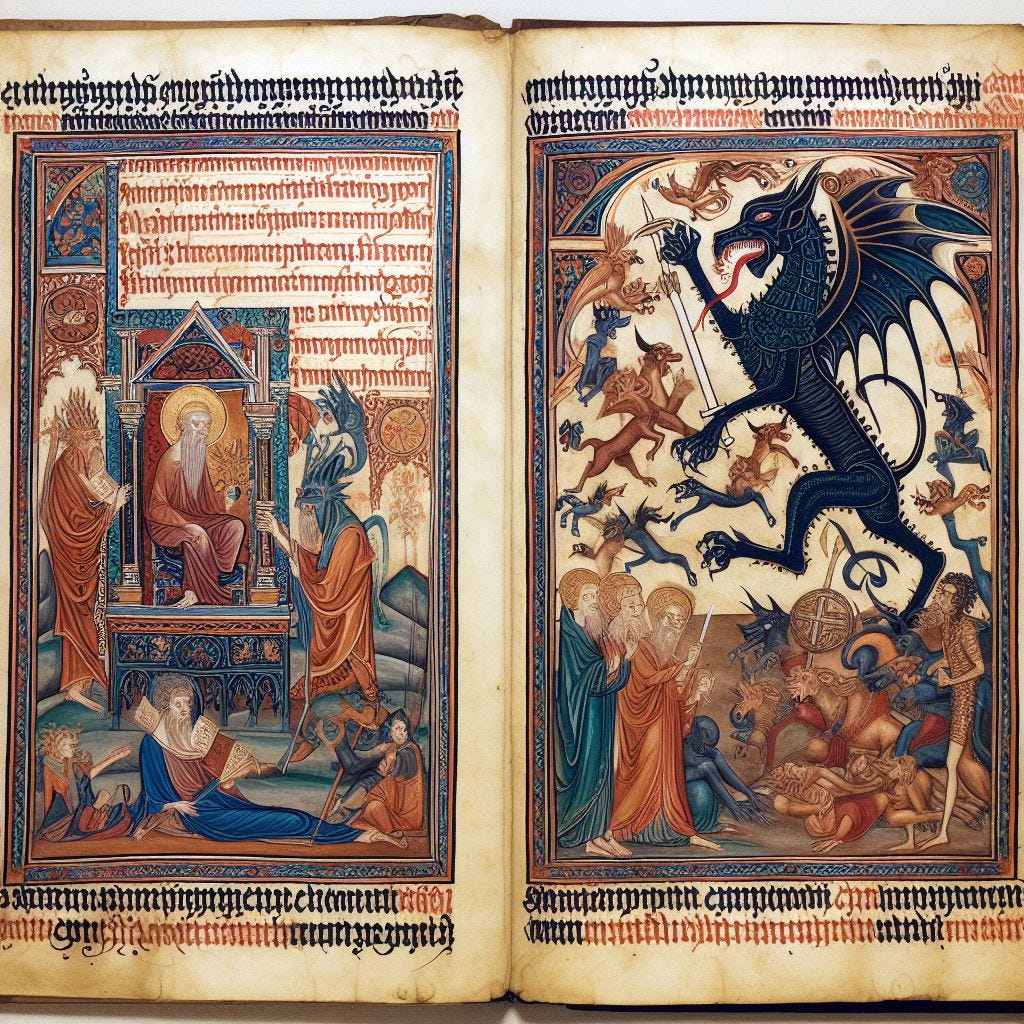

Among the mythological texts originating from Ugarit, the Baal cycle features a significant divine descent to the netherworld (ANET, 138–42). Following Baal's triumph over Yam, the god of chaotic waters, Baal, at the peak of his power, noticed indications of Mot, the god of death, encroaching upon his sovereignty. Seeking to assert his dominance, Baal dispatched envoys to the netherworld to demand Mot's submission, yet Mot summoned Baal to acknowledge defeat and descend to the netherworld. Baal conceded by sending a message of surrender (“I am your slave”) and descended (essentially, he died). His sister Anat discovered his body and interred it atop Mt. Zaphon. Motivated by her love for her brother, she confronted and defeated Mot in the netherworld. Baal revived, returned, and resumed his rule.

Seven years later, Mot provoked Baal again, leading to a fierce battle. The outcome is unknown, but it is presumed that Baal achieved a decisive victory over Mot. The descent of Baal differs notably in its final outcome from the descent of Inanna. Although both are initially compelled to yield to the netherworld's power through death and then evade death's grasp with the aid of other gods, in Baal's myth, the power of death ultimately succumbs to Baal's authority, unlike in Inanna's story where death's power remains intact.

The Ugaritic myth is often linked to the yearly cycle of seasons, with elements in the text suggesting this connection. Baal, the storm god responsible for bringing clouds, rain, and fertility, was believed to descend to the netherworld at the end of spring as the scorching summer commences, only to return to life in autumn, ushering in rain and abundance after the summer drought. However, the final battle with Mot in the seventh year presents a challenge to this explanation and may indicate that the agrarian aspects have been encompassed into a broader mythical framework.

Xella (1987) interprets the myth as a representation of the perpetual struggle between life and death. Baal is depicted as defending the cosmic balance against the influence of death, not eradicating it entirely, but rather compelling it to adhere to boundaries. Mot's pursuit of boundless power, which involves slaying gods and posing a threat to humanity's survival, is thwarted, and death is portrayed as a force that is subdued and restricted by Baal. Xella proposes that Baal's resurrection symbolizes, to some extent, a transcendence of death by the ancient progenitors of the people, although this conjecture may be considered speculative.

The Cycle consists of six main episodes, each of which depicts a different aspect of Baal's mythological journey. The first episode, known as the “Kingdom and Temple of Baal,” tells the story of Baal's divine kingship and the construction of his temple. This episode reflects the Canaanite belief in the close relationship between the divine and the earthly, and it emphasizes the importance of Baal as a powerful and benevolent ruler.

The second episode, “The Contest with Yamm,” is a key element of the Baal Cycle, as it narrates Baal's battle with Yamm, the god of the sea. In this episode, Baal harnesses his divine powers to defeat Yamm and establish his dominance over the natural world. This mythological struggle reflects the Canaanite understanding of the ongoing conflict between chaos and order, and it underscores Baal's role as a powerful and protective deity.

The third episode, “The Conquest of Mot,” portrays Baal's confrontation with Mot, the god of death and infertility. In this episode, Baal is depicted as a heroic figure who overcomes the forces of death and restores fertility to the land. The myth of Baal's victory over Mot reflects the Canaanite belief in the cyclical nature of life and death, and it highlights Baal's role as a life-giving deity.

The fourth episode, “The Descent of Baal,” recounts Baal's descent into the underworld and his eventual return to the land of the living. This episode symbolizes the annual cycle of the seasons and the agricultural fertility that is dependent on Baal's presence. It also reflects the Canaanite belief in the interconnectedness of the natural and supernatural realms, and it emphasizes Baal's role as a mediator between the two.

The fifth episode, “The Defeat of Yamm and the Feast of the Gods,” depicts Baal's final victory over Yamm and the celebration of his triumph by the other deities. This episode reinforces the idea of Baal as a divine warrior and champion of the gods, and it underscores the importance of communal rituals and festivities in Canaanite religious practice.

The sixth and final episode, “The Song of Love,” is a hymn of praise and celebration for Baal's enduring power and divine attributes. This episode serves as a fitting conclusion to the Baal Cycle, as it encapsulates the themes of triumph, fertility, and divine kingship that are central to Baal's mythology.

The Baal Cycle is a rich and complex body of literature that offers valuable insights into the religious and cultural beliefs of the ancient Canaanite people. It provides a window into their understanding of the natural world, the divine order, and the interconnectedness of the supernatural and earthly realms.

Furthermore, the Baal Cycle has had a lasting impact on the development of religious and literary traditions in the Ancient Near East. Many elements of the Baal Cycle can be found in later religious texts, including the Hebrew Bible, and its influence can be seen in the mythology and literature of other ancient societies.

The Ugaritic Baal cycle is a significant and influential body of literature that provides a valuable glimpse into the religious beliefs and cultural practices of the ancient Canaanite people. Its vivid depiction of the struggles and triumphs of Baal, the storm god, continues to captivate and inspire scholars and readers alike, and its enduring legacy is a testament to the enduring power of ancient myth and legend.

The more I meditate on this matter, the more convinced I am that Yahweh is not incarnated in Christ. Rather, it is a more benevolent deity, Marcion was correct to see the disconnect between the historical figure of Jesus and the dubious trickster deity we see in the Old Testament. El had long been displaced from the First Temple, Asherah had been removed, as well as the whole host of heaven, which Baal is chief of the host of heaven; he is the glorious prince of the heavenly host.

The figure of Baal can be seen as a precursor to the image of Jesus Christ in Christian theology. Both figures are associated with divine power and the ability to bring about transformation and renewal.

The first cycle of Jesus’ life in Luke starts with his birth and then presentation at the Temple, Luke 2:1-52. In John, he goes back to the beginning. To Day One, the Holy of Holies in the Temple… In the beginning was the Word and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. So, like Baal, so too is Jesus is presented to us as being Divine and the promised Davidic Messiah.

Jesus is brought to the temple for two good reasons. The first is to show that Jesus follows the customs of Moses, but that it also signals an end to the 2nd Temple. This is because Christ will build a temple not made with human hands, Christ has come to do away with the Tyrant and his rulers. Christ is the Eternal Righteous King of Salem, whose rule will have no end.

In particular, the motif of divine combat in the Baal cycle has parallels in the concept of spiritual warfare in the New Testament. In the Christian tradition, Jesus is often depicted as engaging in a cosmic struggle against the forces of evil and darkness, ultimately triumphing over them through his sacrifice and resurrection. This imagery reflects the belief that Jesus brings about a new order of spiritual and moral renewal, much like Baal does in the Baal cycle.

We see in Mark, how the demons recognize who Christ is, they know because they are from the unseen. Jesus has power and authority over the darker powers because he is not just a mortal man. Look at Psalm 91:13-14: “You will tread on the lion and the adder; the young lion and the serpent you will trample underfoot Because he holds fast to me in love, I will deliver him; I will protect him because he knows my name.”. Who is the lion and the adder? They are essentially the darker powers and the god of the air, which I believe to be Yahweh and his minions. Jesus defeats the serpent and the sower of chaos and death itself. Just like Baal defeated Yamm and Mot. Interestingly, the apostle Paul equates the law to condemnation and death (Romans 3 and Galatians 2).

Jesus was condemned and crucified because they accused him of blasphemy, but their laws were not the laws of the Benevolent El. Rather, they were given by the god who of Edom and Seir. Yahweh was foreign to the Canaanite tribes. Rather, he was “the god of the desert, worshipped by the Kenites and their close relatives before the Israelites”. The Law is a heavy burden that condemns and brings only death. Whereas Jesus brings renewal and Life. This is represented in how both the Canaanite religion and later Christian doctrine emphasize the renewal of creation and redemption of all things.

Both Baal and Jesus are intimately connected to the earth and its abundance, and they are seen as providers of life-giving blessings to their followers. Yahweh, however, is a jealous and unstable deity. He gives and takes away, whilst Christ gives all, just like Baal gave his life to overcome Mot.

Another interesting connection can be seen when Jesus is driven out into the wilderness, where he is tested. I do not think this is coincidental. Yahweh too came from the wilderness, as we have just identified above. Jesus is tested out in the desert, just as Moses and the Israelites were tested for over 40 years. Furthermore, in Levitical law, the scapegoat was sent out into the realm of Azazel on the day of atonement.

Who is Azazel? ‘Azazel’ is the name or epithet of a demon. 2) ‘Azazel’ is a geographical designation meaning ‘precipitous place’ or ‘rugged cliff’ (DRIVER 1956:97–98; cf. Tg. Ps.-J. Lev 16:10, 22 etc). 3) ‘Azazel’ is a combination of the terms ꜥēz (‘goat’) + ʾozēl (‘to go away, disappear’, cf. Arabic zl) and means ‘goat that goes (away)’, cf. ἀποπομπαῖος (Lev. 16.8, 10a LXX), ἀποπομπή (v 10b LXX), ὁ διεσταλμένος εἰς ἄφεσιν (v 26) or caper emissarius (Lev. 16.8, 10a, 26 Vg.), English scapegoat, French bouc émissaire. In order to define the word as the name or epithet of a demon one could refer primarily to the textual evidence: according to Lev. 16.8, 10 a he-goat is chosen by lot ‘for Azazel’ in order to send it into the desert (v 10, 21) or into a remote region ‘for Azazel’. Since lâăzāʾzēl corresponds to lĕYHWH (v 8), ‘Azazel’ could also be understood as a personal name, behind which could be posited something such as a ‘supernatural being’ or a ‘demonic personality’. After this event, Jesus has passed the test and can start his ministry, with the power and keys of authority over the darker powers.

Jesus’ ministry appears to follow the same cycle as the Baal cycle. Just as Baal descends into Hades, so too does our Lord Christ on Holy Saturday, where he overcomes death and gains the keys and authority over death itself. Jesus rises on the third day, just as Baal is raised again, and the power of death ultimately succumbs to Baal's authority. When we call Jesus Lord, do we mean Yahweh or Baal? Please let me know your thoughts in the comments!

I enjoyed this...but when I call Jesus Lord, he is the son of the ineffable God above gods.

You have done a good job with theology clearing up certain contradictions regarding the God of the Trinity. The Baal story has elements similar to the Sophia myth and to Egyptian mythology making it (and the Christ story) far more universal than the Yahweh story line.